中国十二文物(China in 12 Artworks)

On the 3rd floor of the Harvard Fogg Museum, an exhibition called “China in 12 Artworks” takes on the task of presenting the rich cultural history of China by displaying 12 artworks in chronological order, across medium and themes, as opposed to conventional textual studies. As a complementary exhibition to a course currently taught by a Harvard professor in the history of art and architecture department, “China in 12 Artworks” is culturally well-grounded for its deliberate choice of objects and strategy of presentation. To condense three millennia, from the Bronze Age to the 20th century, into 12 artworks, is nevertheless a debatable attempt, and the exhibition poses the challenge of presenting foreign culture in non-native language and context.

The heart of the exhibition lies in its collection of the 12 pieces of Chinese artworks, which is prized by the Harvard Fogg Museum as rare collections among most American Universities. These artifacts are both artistic objects and cultural delegates that mirror the formal traditions, societal values, and cultural themes of China in their correspondent era. All of the objects on display are originally from China, which can date back to as early as the 4th millennium. Thus the authenticity of the objects offers the audience a chance to look at Chinese history through its fragments in artistic forms. For example, one of the oldest objects, the bronze ritual bell (Bo Zhong), is documented to be from the Zhou dynasty, Warring States period, 475-221 BCE. The Bo Zhong encompasses the ritual traditions, aesthetic values, and mythological norms of that time period: it is a musical instrument for special occasions such as funerals and weddings, which are the main components of cultural life in the Zhou dynasty. In addition, by examining its design—stylized dragon and snake decoration, with handle in the form of birds—it can be read that the knowledge of artistic formal traditions, since dragons, snakes and birds are typical choices of animal in ancient Chinese art that symbolize natural forces(ying/yang). Furthermore, such design embodies the societal value that is oriented around the worship for the cosmos, which is a cultural foundation that ties the ancient Chinese society together.

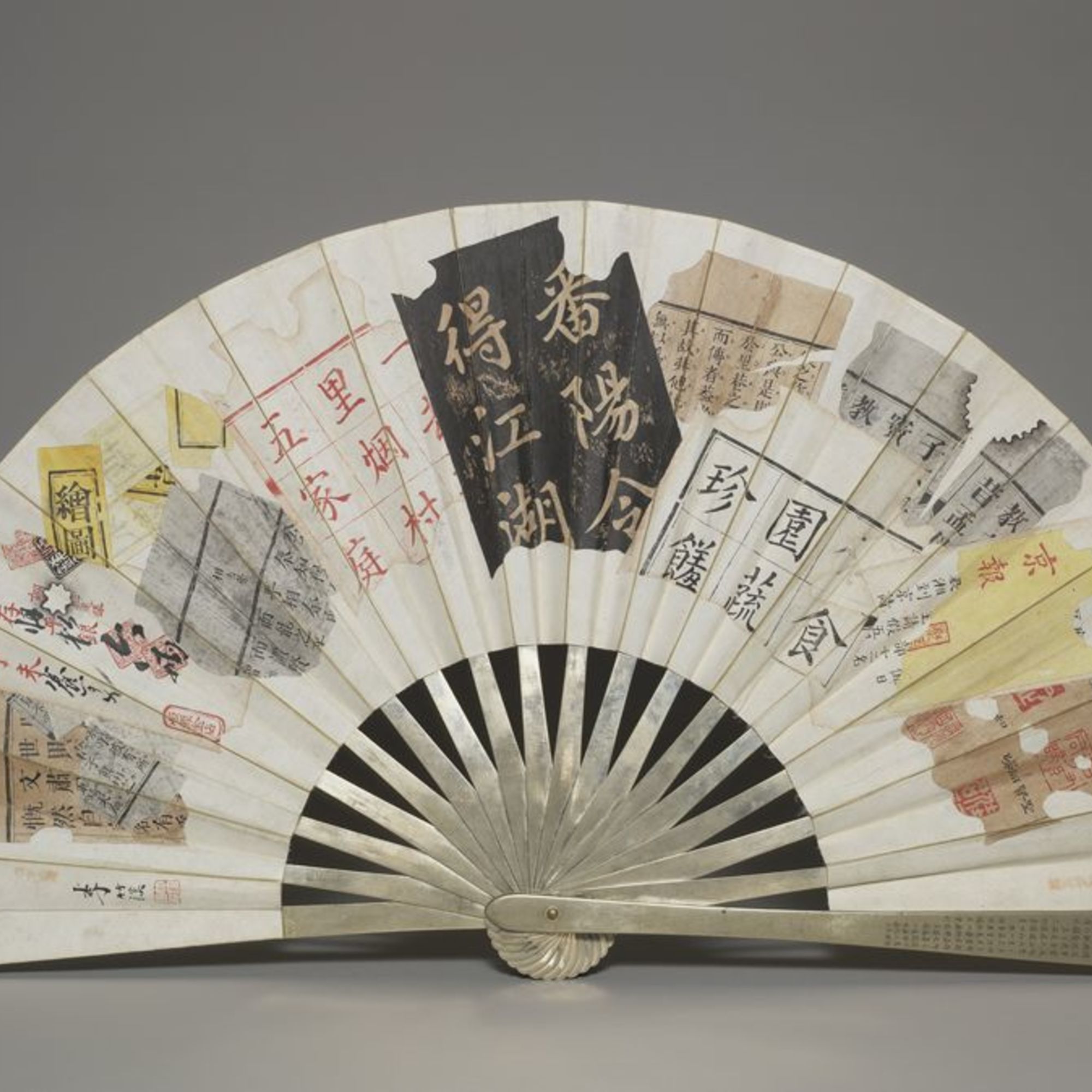

The other 11 artworks can be read similarly with respect to their representation of history. For instance, moving on from the Bo Zhong, the audience will learn about the Wu dynasty in the late 3rd century through the “Hunping” funerary jar, the Qing dynarty(1644-1911) through the Moon and Melon painting, and the early 20th century through the collaged fan. Together these 12 artworks compose a visual textbook, each being a unit of certain time period that immerse the audience in the historical context, while occupying a physical space in the exhibition that confronts the audience with their solemnity and dignity.

The strategy of assigning time periods to each one of the 12 artworks is both a choice out of academic inquiry, and also a choice influenced by traditional Chinese ideology that endorses unification and harmony. The exhibition is unprecedented in its effort of condensing a history of 4 millenniums into 12 artworks-- why not assign 15 artworks or 20 artworks? The reason behind this deliberate choice, besides the limitation of the University’s collection and the need to serve the corresponding art history course agenda, is the exhibition’s nature to represent Chinese history and artistic traditions. Nor only does the exhibition achieves this goal by presenting authentic, informative artworks, but also by presenting them in the “Chinese” way. This is especially clear from the independent website that compliments the exhibition and the corresponding course. On this website, the 12 artworks are compared to more Chinese artworks, categorized and ranked by artistic elements such as brushwork, subjectivity effect, narrative and so on with great clarity and systematic organization. In a separate tab of case studies, the 12 artworks are aligned horizontally in circular icons, and to click open each one requires the password of “8888”, which in Chinese traditions calls for luck and fortune. All of these design speaks to the Chinese tradition of categorization and unification, and highlights the balance between 12 different objects of the same culture, with a finishing touch of superstition that is one of the hallmarks of the Chinese culture. This shows another level of authenticity that is embodied by the method of , which solidifies the exhibition’s mission to present Chinese culture and history. Although obscure, the small choices that mirror the Chinese cultural traditions are indispensable in forging an authentic voice for the 12 artworks and the history behind them.

Nevertheless, it is debatable whether each of the 12 artworks does the time period it represents justice. It’s better to say that the 12 artworks are only meant to give the audience an access to the history rather than to definine the history as 12 physical embodiments. A more challenging question, however, is that the voice forged by the exhibition, the voice that animates the history and the culture behinds the 12 Chinese artworks, speaks English. Such is a dilemma that commonly imposes on studies of foreign culture. Although “China in 12 artworks” puts its exhibition in the Chinese context, the language barrier is far from invisible. Moments of inaccessibility are frequently encountered when the artwork includes complimentary texts or is composed of texts in Chinese. The same plight occurs when the website provides the reader with external sources and references, many of which are in Chinese. Despite the effort put into the exhibition to make the objects and accompanying texts as original as possible, the audience may still be one step away from fully absorbing the cultural nuance behind the 12 artworks. The metaphors that are grounded in ancient Chinese poetry, the historical context of dynasties that lives in bedtime-fables, the beliefs and superstitions that are practiced by Chinese festivals… These are the rich undertones of the Chinese culture that any single exhibition can hardly succeed in resenting.

Overall, “China in 12 artworks” is a bold undertaking and an exhilarating opportunity for the audience as well as the University. Across the barrier of language, time, and cultural context, the exhibition allows the audience to catch a glimpse of ancient China in its historical fragments with breath-taking beauty.

Reference

China in 12 Artworks, http://www.chinain12artworks.com/#!blank/c1xfa

Harvard Art Museums, http://www.harvardartmuseums.org