Refracted Culture: Radio Contact's Cultural Wavelengths

Culture interacts with society like light refracting through glass. A single ray, like a new idea or piece of technology, can strike society one way but be dispersed on the other side of society’s looking glass across a new set of political, technological, and cultural wavelengths. In the most literal sense, this refraction can take place even at the level of an individual’s personal looking glass as demonstrated by author Vladimir Nabokov’s own window on the world. In his autobiography, Speak, Memory, Nabokov reflects on an oriel from his childhood home whose angles could play visual tricks on the snow and whose panes could initially offer him “nothing to watch save the dark” until the ideas of the time dispersed society’s Revolution across Nabokov’s view in the form of “various engagements…and my first dead man”(Nabokov, 89). At Harvard University’s Putnam Gallery, items on display from Harvard’s Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments demonstrate the refraction of culture on a broader scale as visitors walk through the successive wavelengths of scientific ingenuity unleashed by the intersections of science and culture through the ages. Serving as the public face of the History of Science Department, Putnam uses the primary sources of this field as a lens into the history the field explores and the methodology it uses. However, the ample space of Putnam’s “Special Exhibition Gallery” on the second floor allows visitors to walk through the application of this methodology to a specific topic: the radio. Through the lens of this subject, Putnam’s display tactics and pedagogy are repurposed to present a visual argument throughout Radio Contact: Tuning In to Politics, Technology, & Culture that “contact” across scientific and cultural spaces be redefined. In arguing for a reinterpretation of radio’s “spaces” and “contact,” Radio directly confronts visitors with these issues by capitalizing on the actual spaces and points of contact the gallery makes possible as means to tune visitors into the historical refraction of scientific and cultural wavelengths that generated different experiences and spaces of contact for radio practitioners and aficionados.

To tune into Radio Contact’s argument, it is important for visitors to be on the same wavelength of methodology that follows them from the Putnam Gallery up to the “Special Exhibition Gallery.” Although each gallery has a different goal, the former lays out a thematic display and methodology that are crucial to the argument of the latter. The multidisciplinary nature of History of Science gives it the capacity to connect academic spaces. In investigating contact between these spaces across history, the agency of historical actors within these processes becomes a theme. In its analysis of the spaces, contact, and agency connected to its subject, this methodology is inherent to the argument made by the written and physical components of Radio. However, one must look at the explicit exhibition of this methodology in the Putnam Gallery to understand how its implicit repurposing so effectively Radio’s point. As part of the History of Science Department, the Putnam Gallery displays a sampling of the historical scientific instruments the field uses as primary sources. These objects are organized according to their respective scientific themes, like navigation or sound, and chronologically to give a sense of how these historical narratives intersect with their scientific counterparts over time. In doing so, a reciprocal relationship is established between the instruments and the cultures they belonged to. Take for example the narrative that portrays sound. The first instruments follow basic attempts to create scientific instruments for the standardized study of sound. The next instance in which sound is featured is through the lens of “The Science of Sound in Wartime” which features instruments Harvard professors used to study sound during WWII. The aspect of a cultural “lens,” in this case war, is common elsewhere. It is here that we come across methodology manifested in the display format: prisms. Given the nature of History of Science, its investigations refract a topic across the wavelengths of its multidisciplinary roots. In the instance of sound, this is exemplified by the lens of wartime, which refracted the possibilities of sound technology across a larger spectrum. Putnam’s displays physically argue for this methodology of exploring multidisciplinary topics by shaping all of the display cases to look like prisms. As one walks through the gallery, the scientific and cultural ideas and themes are refracted from the prism representing one period to the next. The thematic display layout, methodology, and reciprocal relationship between established between science and culture in the Putnam Gallery serve as vital undercurrents to Radio Contact’s argument.

Radio follows in Putnam’s footsteps to facilitate the multidisciplinary thinking needed to create contact between the spaces related to radio. As a creative work and as a cultural construction, Radio Contact applies Putnam’s display tactics and visual portrayal of its methodology as the foundation of its exhibit before expounding on them to further its specific investigation. In this way, Radio is able to argue for the expansive nature of contact across spaces made possible by radio through the physical immersion of visitors in those spaces and forms of contact. Through its focus on history, the exhibit is able to use time as a space and represent the relevant scientific and cultural points of contact across it. The organization draws on Putnam’s concept of refraction in its methodology and physical display. Rather than simply organize the content chronologically, Radio follows the multidisciplinary roots of History of Science by grouping the content into three displays, each articulating a different narrative created by the continual refraction of scientific and cultural wavelengths off of each other. In doing so, a sense of agency is introduced that transforms otherwise disjointed historical events into stories that reflect the agency and contact involved in the interactions between science and culture. The exhibit uses its space to further this methodology as the two historical narratives featured at the front of the exhibit build towards common themes that yielded the last narrative about the history of modern broadcasting featured at the back of the exhibit. By borrowing the organizational structure of Putnam, Radio creatively constructs the multidisciplinary space that expands the academic horizons it visitors can journey through while cohesively articulating the narratives found across those expanses opened by radio. However, these narratives do not end simply when visitors have reached the last piece of text or object. Dr. Sara Schechner, curator of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, hopes that when visitors depart and find themselves staring at “new” technology like their iPhones or Sirius XM Radios, they will be filled “with a sense of ‘Huh, I’m back to the beginning”(Schechner).

Radio’s point of departure from Putnam that facilitates the different argument it makes is the different use of display cases to “refract” its investigative inquiries. While Putnam’s prisms make the themes and methodology of History of Science the gallery’s focus, Radio’s exploration of space and contact displays the application of these themes and methodology to the scientific and cultural wavelengths of interest behind glass on either side of the gallery while reconstructing the cultural spaces and technology generated by the refraction of these wavelengths. The three creative vignettes that represent these cultural spaces demonstrate the shift from the themes and methodology of History of Science demonstrated in Putnam to the use of those elements as part of an argument. By putting the selected scientific and cultural objects and facts in conversation with each other, Radio yields a discussion that breaks free of Putnam’s methodological “prisms” and leaves visitors with a new scope to the space, contact, and agency of the topic at hand: both intellectually and in its physical portrayal. This validity of this new environment is argued through the physical reconstructions of it.

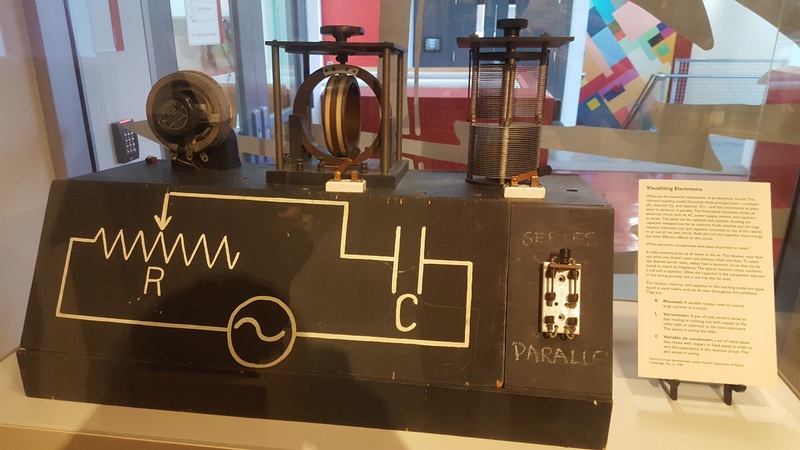

The vignettes of “Listening,” “Tinkering,” and “Broadcasting” each present a specific narrative that reflects the wider scope of the space, contact, and agency it contains when it is refracted into its scientific and cultural wavelengths, represented by the instruments and objects behind glass on either side of the gallery. The vignettes physically reconstruct interactive settings that represent President Roosevelt’s Fireside Chats, the “ham” shack of ham radio, and the broadcasting booth of modern radio. Each one serves as a familiar reminder of a scientific and cultural intersection whose components are refracted across the accompanying display cases. Crafted to portray the “point of view of a radio aficionado through the ages,” curator Dr. Schechner says the spaces she seeks to emphasize are those that emphasize the “real passion and practice of it”(Schechner). This emphasis on agency and action across the spaces occupied by radio aficionados permeates the exhibit and the way it portrays the shifting spaces of radio.

No space, no contact, no agency is ever inhabited completely by science or culture as demonstrated by Radio’s vignettes and expanded on through its display cases. Although “Listening” portrays the limited agency of consumers as they could merely sit back and receive the new technology offered and the cultural available over those limited wavelengths, it demonstrates the way new spaces for discourse, like FDR’s fireside chats, emerged along with a new sense of connection between those now in contact. “Tinkering” explores the science behind radios and the development of that technology, but does so through the cultural lenses of wartime efforts and later the confrontation between governmental institutions and individual practitioners, like those who built their own “ham” radio stations.

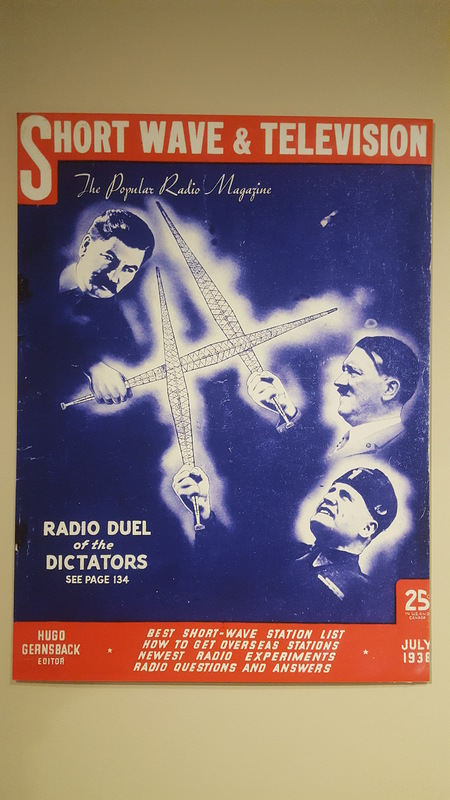

Nowhere is Radio’s reexamination of practitioners in their places more visible than in “Broadcasting.” “Broadcasting” showcases the cultural and scientific wavelengths dispersed from the refraction between the “Listening” consumers and those “Tinkering” for control of the airwaves. Unlike the other narratives that follow a linear setup to the left and right, “Broadcasting” occupies the back third of the gallery with a reconstructed broadcasting booth against the rear wall and empty space in the middle around which are samples of the different voices that have found a space and agency on the radio. This shift in display setup from a linear historical conversation to being physically surrounded by all different historical voices is demonstrative of the specialized and expanded world made possible by radio, from internationally broadcasting the intolerance of Nazi Germany to finding a voice for the offshore rebels of Pirate Radio. As the exhibit’s curator phrases it, “Now we have not just one voice for everybody, but many voices to share with everybody”(Schechner).

The argument that literally rings in the ears of visitors until the moment they leave is the changing directionality and agency of these spaces and points of contact. Although “Broadcasting” physically showcases different voices that have found their place on the radio, the disjointed manner in which they are displayed side by side does not give a sense of the relation between them. However, the presence of radio broadcasts throughout the gallery give a sense of the exhibit that is first spatial and then psychological. The speakers, positioned throughout the gallery above the displays, play broadcasts related to the objects they correspond to. The audio clips play on a rotating. Because they are positioned throughout the gallery and above visitors they give a unique sense of direction and agency. Experiencing the sound from above gives one the sense of being engrossed in that historical moment while from a distance it has an echoing feeling of authority or longing to be remembered through the ages. What is most striking is the way audio clips give a sense of spatial relation and agency between each other. As they stop and start a sense of call and response is developed as if the air through which they sound off belong to everyone and no one at the same time. The audio clip that echoes from one corner gives it the sense that it resonates from a different community than the comforting one of FDR above one’s head that chimes in next. Radio displays practitioners in their places, but its sounds establish their own place.

Curator Dr. Schechner explains that when it came to organizing the interdisciplinary mix of science and culture presented in Radio, she wanted to demonstrate that “Life is messy, and history is very layered, so I wanted to comingle these things because visitors can get it without that mix elsewhere”(Schechner). That “mix” of the space, agency, and points of contact radio creates across its scientific and cultural wavelengths becomes her argument that radio occupies more than what either of those disciplines recognize and does so in a more dynamic way. Founded on the methodology and display mechanisms of the Putnam Gallery, Radio Contact shines a spotlight on its topic through the pedagogy of History of Science with the additional use of physically reconstructed vignettes, spatial layout, and auditory layout. Schechner’s mix of curatorial tactics leaves visitors tuned into a new awareness of the cultural and scientific wavelengths emanating from radio in their lives.

Works Cited

Nabokov, Vladimir Vladimirovich. Speak, Memory; an Autobiography Revisited. New York: Putnam, 1966. Print.

"Radio Contact." Interview by Sean Kinyon. Dr. Sara J. Schechner. Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Cambridge, MA, 15 May 2016. Television.