Religion and Science in the Great Mammal Hall

“To me it appears indisputable, that this order and arrangement of our studies are based upon the natural, primitive relations of animal life… being in truth but translations, into human language, of the thoughts of the Creator” ~ Louis Agassiz

Just north of Harvard Yard, nestled between the Science Center and the Divinity School, stands the impressive though often overlooked Harvard Museum of Natural History. Composed of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, the Herbaria, and the Mineralogical Museum, the consortium’s location underscores its history at the crossroads of science and religion at Harvard University during the late 19th century. This conflict is highlighted by the Great Mammal Hall located in the Museum of Comparative Zoology. Here, visual manifestations of faith in a Divine Creator are met head-on by exhibits meant to corroborate Darwin’s theory of evolution.

Upon entering the Great Mammal Hall, one is immediately struck by the grandeur impact of the display. In total, the MCZ holds over 21 million species, and this gallery exhibits some of the most magnificent of those specimens. Imposing bison, elk, a dugong, and even a hippopotamus fill the floor of the 40 by 70 foot room, along with hundreds of other species from every order of mammals and every continent of the globe (Wallace 2.) A twenty-foot tall giraffe draws the eye upward to the three massive whale skeletons hanging from the high ceiling. Beholding such sheer diversity, all illuminated by natural light streaming in through large windows, leaves the viewer with amazement at the fecundity of Nature.

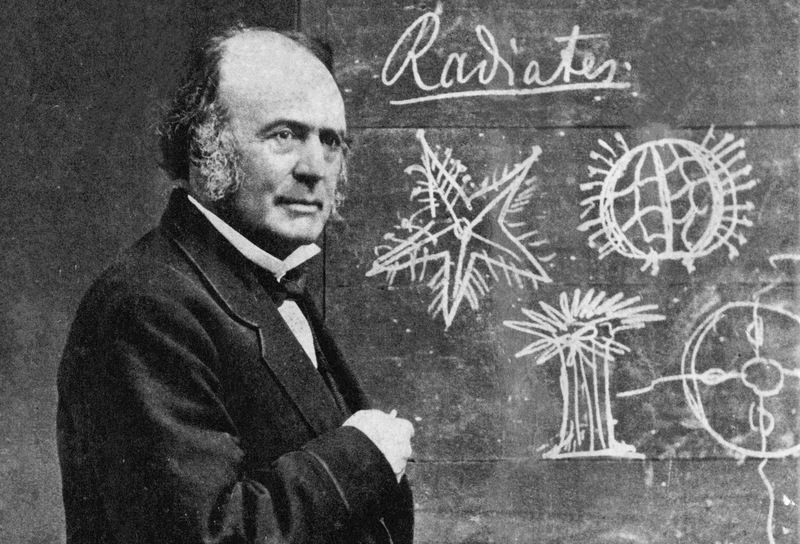

Indeed, this reaction is what founder Louis Agassiz had intended. In 2009, to honor the 150th anniversary of the MCZ, the Great Mammal Hall was renovated to reflect Louis Agassiz original vision – that is, to awe visitors with the splendor of God’s creation. Agassiz believed that through studying the natural world, he could better comprehend “the thoughts of the Creator” (Bebergal 2.) With the founding the Museum of Comparative Zoology in 1859 – ironically the same year that Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species – Agassiz hoped to glorify God through science. This aim is evidenced not only through the diversity of the animals displayed, but also through their organization.

Unlike natural history museums in Europe and elsewhere in the United States, which were centered on cathedral-like galleries containing cases crowded with thousands of specimens, the Great Mammal Hall is relatively small with fewer specimens. This smaller scale, Agassiz argued, allowed for greater organization by taxonomy as well as geography (Wallace 4.) In contrast to museums such as the American Museum of Natural History in New York, where animals are presented along with reproductions of their natural habitats, the exhibits at the MCZ comprise glass cases containing taxidermies, often alongside their accompanying skeletons. By eschewing the imitation of life and placing the animals in stark juxtaposition with neighboring specimens, the relationships between similarly classified organisms – such as the giraffe and its likewise long-necked cousin the okapi – becomes obvious. To Agassiz, this immaculate organization of nature was irrefutable proof of a Divine Creator (Bebergal 3.) But this devotion to taxonomy did not extend to evolution: Agassiz was notably resistant to Darwinism, believing that such a theory belittled the wisdom of God. Species, he argued, did not change over time, but rather had been perfectly designed at the moment of Creation.

Louis Agassiz’ insistent rejection of Darwin’s now widely accepted theory was betrayed by his own son, Alexander Agassiz, who succeeded his father as director of the MCZ upon Louis Agassiz’ death. Though the current Great Mammal Hall largely reflects Agassiz Sr.’s original design, one exhibit in particular sticks out. Under the staircase leading up to the second floor stand five skeletons: a macaque, an orangutan, a chimpanzee, a gorilla, and Homo sapiens (Bebergal 2.) Arranged by decreasing height from left to right as the staircase slopes above them, the case displays a literal “descent of man,” a direct homage to Darwin’s book on his theory of human evolution. Though curated by Alexander Agassiz in the late 19th century, the exhibit is deeply reminiscent of the famous 1965 illustration The March of Progress, which shows several hominids lined up, through gibbon to ape to human, as if marching from left to right. Described by evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould as “the canonical representation of evolution – the one picture immediately grasped and viscerally understood by all,” the graphic may well have been inspired by the MCZ’s exhibit (Gould 127.) In any case, the display’s impact is equally as forceful, conveying an explicit message about the museum’s loyalty to the prevailing theory of the day.

The visitor walking into the Great Mammal Hall, arrested by the magnificence of the exhibit, experiences a suspension of belief, upon which the specimens project two contrasting views about the origin of life. Though similar evidence is used to promote both ideas, it is up to the viewer to interpret the exhibit: did species arise through the deliberate act of God, or through the random modifications of nature and time? In this way, the Great Mammal Hall serves not only as a scientific gallery, but also an artistic display. It delivers facts, but through the organization and interpretation of those facts communicates diverging opinions about religion and science that have continued to fuel debate into our modern age.

Works Cited

Peter Bebergal, "With Agassiz, Darwin and God in a Collection's Inner Sanctum," Harvard Divinity School Bulletin. 2008, vol. 6, no 2S.

Stephen Jay Gould (and Rosamond Wolff Purcell), Finders keepers, New York: Norton, 1992. pp.124-137.

Alfred Russell Wallace, Fortnightly Review 48 (1887): 347–59.