Between the reader and the text:an aesthetic reading of "River Snow", an ancient Chinese poem

How are poems read? What is the reader’s experience in the reading of poems? In his book “the reader, the text, the poem: the transactional theory of the literary work”, Louise M. Rosenblatt argues that the reading of poems is a collaborative action between the text and the reader. Rather than having one of the two as the authority in determining the reading of a poem, she proposes that readers and the text interact mutually with each other in the process--“’the poem’ comes into being in the live circuit set up between the reader and ‘the text’”(p14, Rosenblatt). Rosenblatt treats the poem as an event, in which the readers draw stimuli from both the text and their own experience, in addition to the environment, their awareness, and many more contextual elements. Thus, the text is not the only dominating factor in the reading of a poem, but rather the reader, the text, and everything in between. In Rosenblatt’s words, “a specific reader and a specific text at a specific time and place: change any of these, and there occurs a differernt circuit, a different event—a different poem”(p14, Rosenblatt).

Rosenblatt’s book, “the reader, the text, the poem: the transactional theory of the literary work”, was published in 1978. The book became very influential in promoting the reader-response literary theory that focuses on the reader’s active engagement in reading beyond the text and the author. What happens, however, when the theory produced by an American scholar in the late 20th century is tested on an ancient Chinese poem from the year of 805? What’s the reader’s experience in “transacting” with the text, using a different language? In order to answer these questions, this paper will examine the classical Chinese poem “River Snow” based on Rosenblatt’s theory. The paper will later demonstrate, that the western modern literary theory can be practiced on an ancient Chinese poem despite the language difference, as we take a detour, starting from the text, to its visualization, and arriving at an interpretation. In fact, it is because of the language barrier which prevents us from dwelling in the text, that promotes the “transaction”—a reading that is less an input of text but more an output of old memories and experiences.

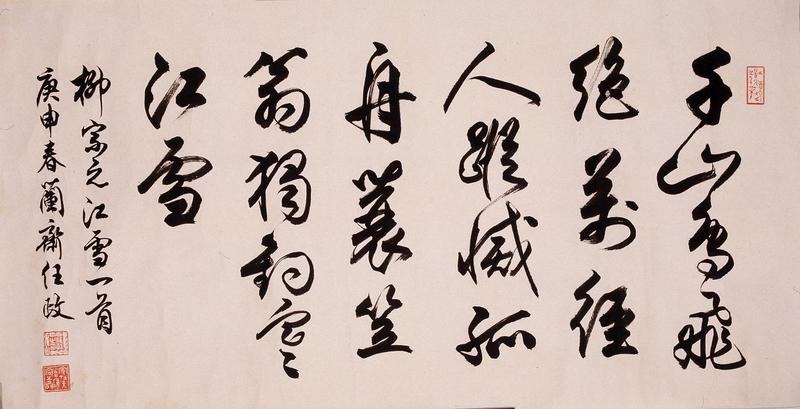

River Snow” is a five-word-poem written by one of the most revered Chinese poet and philosopher Liu Zong Yuan(773-819) from the Tang dynasty, whose more than 600 poems and essays are widely celebrated as classics among the rich collection of Chinese ancient literature. His poems are famous for their plain, simplistic style and intense philosophical reflection behind, which exemplifies a high level of mastery over the Chinese language. “River Snow” was composed in the year of 805, the Yong Zheng Yuan year of the Tang dynasty during which a political revolution led by Liu Zong Yuan’s party took place but was shortly terminated by other political forces. As a result, Liu Zong Yuan was exiled to an under-developed, discrete town called Yong Zhou, where he spent 10 years of hardships before becoming appointed again by the central government, and “River Snow” is often viewed as Liu’s testament for the life’s disfortune. To start with, here’s the original poem of River Snow and its English translation:

|

江雪 千山鸟飞绝 万径人踪灭 孤舟蓑笠翁 独钓寒江雪 |

River Snow A thousand mountains, no sign of birds in flight; Ten thousand paths, no trace of human tracks. In a lone boat, an old man, in rain hat and straw raincoat, Fishing alone, in the cold river snow. |

Now that the rudimentary information is obtained from a poem, what can the reader do with it? In Rosenblatt’s theory, the text is a stimulus activating elements of the reader’s past experience—his or her experience both with literature and with life. Taking the first line of “River Snow” as an example, “A thousand mountains, no sign of birds in flight”, one may envision a landscape shrouded by snow, with black, barren mountains thrusting through the earth and then stands in silence, the silence of wilderness in a winter evening when not even a bird can be seen. The second line follows, “ten thousand paths, no trace of human tracks”, which zooms into the view of the mountain where there are thin paths among the stones and shrubby, but not footprints can be found. These two opening lines takes the reader to a winter wilderness of absolute silence and stillness, as one thinks of the quantity “thousand” and “ten thousands”, as well as the nature agents of “mountains” and “birds”. In recreating the sensation, the reader synthesizes a space that lives outside of reality but also outside of the text—a transient space that lives at the moment of reading, the moment when the reader think of the whiteness of snow covering the mountain, the death silence beyond the cliff, the bit of the coldness on exposed skin, the story he once read about winter, the video he saw that is filmed in the mountain, and many more.

To present the result of this synthesis more tangibly, a painting is created to physically embody the idea of this paper. The information obtained from the text, in addition to personal experience and sensory memories, have all contributed to the conscious choices made during the creation of the painting. For instance, only black ink is used throughout the painting, in the hope of embodying the starkness of the scenery. Fast, sketchy strokes are made to trace parts of the mountains’ outline, with adjacent areas dabbed by watery grey, which are meant to create dimension for the plane view. Additionally, the blankness aside from the strokes are left behind to give the painting a minimalistic style, and to present a sense of grandness.

Similar ways of reading can be applied to the last two lines of “River Snow”, so that the addition of information becomes the addition of visual elements on the paper. The solitude of the fisherman becomes tangible as one reads through the last two lines, and relate the information with a feeling of isolation, a memory of being alone in the wilderness, the sensation of fishing on a frozen river, or the impression of an old man whose only belonging is his fishing boat. Proceeding from here, the stimuli lead to the artistic choice of using white pigments in thick globs in representation of the frozen snow, and a black, filled figure as fisherman, detached from everything else on the canvas, and floating on top of chunks of void.

Combing the two parts together, the poem “River Snow” becomes fully embodied in a visual product that is the consummation of the text and the reader’s own input. The author Liu Zong Yuan wrote the poem at the time when he was banished from court because of political complication, and a Chinese literary critic would lecture about “River Poem” with respect to the literary tradition in ancient China on writing about banishment from court, or using natural imagery to embody life philosophy. However, as the reader start from the text, transact the information with his or her experience or imagination, and consolidate the result by reconstructing the poem visually, the final “reading” is equally fruitful. As an “aesthetic reading” in Rosenblatt’s theory, such practice encapsulates not only the author’s own intention and experience, but also the reader’s intention and experience. The reading of a poem, is thus an event, more invigorated than text, and more transient than life.

By translating the text into visual language, the “transaction” of Rosenblatt’s theory is performed though the process of choosing visual components and techniques, during which the reader synthesizes the text with what he or she brings to the text. More importantly, the reader need not have the perfectly translated poem to perform an aesthetic reading, since visualization can be based on intuition, imagination, and sensory experience that are independent from the text. In fact, it is an ancient Chinese literary tradition to construct poems and non-fictional essays pictographically, as Kuo His, a Chinese Northern Sung Landscape painter says :“Poetry is painting without form, painting is poetry without form”. Therefore, it should be no surprise that “River Snow” can be read visually, even though an orthodox reading would have to work through the literary devices, the metaphors, implications and so on. As it turns out, the language difference between ancient Chinese and modern English that prevents the reader from exercising traditional text-based reading, reversely promoted the visualization of the text, henceforth allowed the “transaction” in Rosenblatt’s theory to operate even more thoroughly.

Work cited:

100 years of Chinese piano music, exhibition, 2015, the French Gallery of the Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library

The Reader, the text, the poem: The transactional theory of the literary work. 1978. Rosenblatt, Louise Michelle. Southern Illinois University Press. Feffer & Simons, Inc.