Redefining American Blackness: Kwanzaa as an Invented Tradition

Eric Hobsbawm’s “Mass Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914” explains an invented tradition as a cultural practice designed to resemble an ancient tradition and intended to foster a sense of nationalism (Hobsbawm 263-265). The United States has benefited from the invented tradition repeatedly throughout its history, and has used holidays like Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Independence Day as devices for instilling unity among its increasingly multicultural populations. Kwanzaa, though a holiday created in the United States, is not meant to teach American nationalism to a culturally diverse society; rather, it promotes a specific kind of culture for a subset of American people, and unites them for reasons that go beyond nationalism. Kwanzaa unites its adherents in the struggle for sociopolitical power and racial pride in a nation that attempts to marginalize and discredit their rights and experiences.

Dr. Maulana Karenga, an African American civil rights activist and African studies professor from Maryland, created Kwanzaa in 1966 in an effort to establish pan-Africanism among African Americans during the Black Power movement of the sixties. The movement, a response to the social injustice, oppression, and discrimination faced by African Americans, corresponded to an attempt to reclaim heritage and, in doing so, overthrow white power by ending cultural oppression. Karenga, influenced by Malcolm X’s Black Nationalist theories based on separatism, black independence, and pan-Africanism, was one of the leaders of the Black Power movement. With Kwanzaa, he aimed to change African Americans’ mindsets from Western-based, or mentally-enslaved, to Afrocentric, or self-determining. In this way, the Afrocentric mentality could develop a communal sense of responsibility and unity within the African American population that would inherently release them from white oppression and secure their sociopolitical liberation.

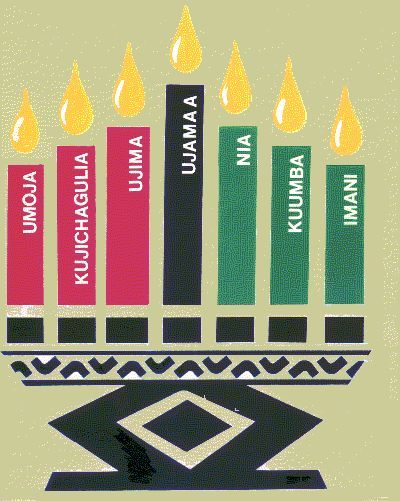

Karenga took most of his inspiration for Kwanzaa from the first fruit celebration, a tradition commemorating the harvest, practiced in many parts of Africa. Adapting the seasonal holiday for an African American audience, Karenga incorporated core values of ingathering, commemorating, reverence, recommitment, and celebration into Kwanzaa and came up with seven principles designed to be “the matrix and minimum set of values African-Americans [needed] to rescue and reconstruct their life in their own image and interest and build and sustain an Afrocentric family, community, and culture” (Flores-Peña and Evanchuk 282). He also emphasizes the importance of African philosophy in designating the seven principles represented on the Kwanzaa kinara, or candle-holder. These principles consist of umoja (unity), kujichangulia (self-determination), ujima (collective work and responsibility), ujamaa (cooperative economics), nia (purpose), kuumba (creativity), and imani (faith). Each of these legitimizes the significance of Black Nationalism and the struggle for African American rights in the United States. Karenga calls for African Americans to self-identify as a united group of people struggling towards the same goal, encourages their ability to choose their own fates despite the interference and overarching dominance of an oppressive society, and reminds them that they have a responsibility to band together and fight for each other in order to make long-lasting progress. He also eschews the capitalist mentality and with it, Western philosophy, instead advocating for collective goals and production based on a mindset that builds on the ideals of brotherly love, loyalty, and determined persistence. Supported by an African sociohistorical perspective, Kwanzaa, according to Karenga, “serves to reaffirm the bonds between [blacks in America] as an African people” (Flores-Peña and Evanchuk 283) and “reaffirms [their] commitment to the African culture and gives [them] a time to come together…[they can] measure [themselves], the authenticity of [their] lives, by how rooted [they] are in [their] tradition. Kwanzaa is a celebration of the good, celebration of the good of [their] lives], the good of [their] history, the good of [their] culture, celebration of the good of life, the good of love in each other, building with each other, the good of history marching towards the ultimate goal of full human freedom” (Flores-Peña and Evanchuk 283).

As Karenga had hoped, Kwanzaa instilled within many African Americans a deep sense of culture and a historical connection to their African pasts. The holiday became strongly associated with Black Nationalism, and in the years following the collapse of the movement, represented a resurgence of black pride. Black people in Africa, the Caribbean, and Canada have adopted Kwanzaa and celebrate it as a way to honor their heritage. As an invented tradition meant to surpass patriotism among adherents and additionally spur a call to action, it succeeds in evoking initiative in African Americans even today: by provoking Afrocentric mindsets and encouraging black pride, African American celebrators of Kwanzaa unite themselves with the African diaspora and pay homage to their community and origins.

Works Cited

Flores-Peña, Ysamur, and Robin Evanchuk. “Kwanzaa: The Emergence of an African-american

Holiday”. Western Folklore 56.3/4 (1997): 281–294. Web...

Hobsbawm, Eric. “Mass Producing Traditions, Europe: 1870-1914”. The Invention of Tradition.

Ed. Terence Ranger, Eric Hobsbawm. Cambridge University Press, 1983. Print.