Blog-ometry?: Learning in the Internet Age

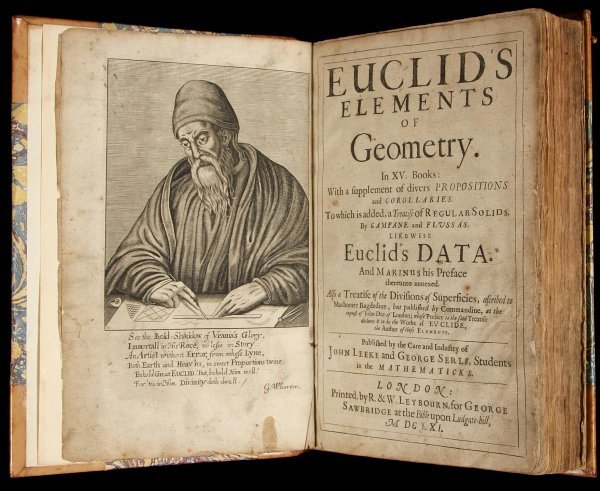

Of the mathematical sciences, the field of geometry is perhaps the most associated with visual representation. If one were to lead a word association game with the term “geometry,” common responses would likely include “shapes,” “circles,” “squares,” “rectangles,” “triangles,” and the like. Indeed, geometry is the mathematical bridge between the world of numbers, measurements, and formulae and our three-dimensional world of objects, shapes, and images. However, the viscerally visual nature of geometry was not always the case. The man who is today considered one of the fathers of geometry, Greek mathematician-philosopher Euclid, published his Elements of Geometry with nary a diagram, picture, or color. He wrote Elements in 300 BC as a methodical series of “proofs” of theorems and postulates that could then be used for more complicated mathematical explorations.

Though Euclid’s Elements was written for the purpose of disseminating these proofs to a wide audience, its mathematically precise text made it difficult for the average reader, such as the lay mathematician or student, to digest. However, it persisted as a paragon of geometric education given that there had been nothing clearer. This changed in 1847, when Oliver Byrne performed the first remediation of Elements, or at least the first six books of the series. Byrne replaced much of the text with colorful diagrams—the precursor to our current understanding of geometry as a field of study that we can represent visually. This retooling has opened the floodgates of geometric teaching, so to speak, and has led to hundreds of thousands of geometry textbooks, now all using the same principle of quite literally illustrating complex mathematical concepts with colorful diagrams.

Though Oliver Byrne's edition of the first six books of Elements maintains the codex form, it is certainly akin to a remediation of the original, given its emphasis on colors, shapes, and diagrams rather than text. As evidenced by his inclusion of "for the greater ease of learners" in his title, Byrne repurposed Elements in the way he did because he wished to build on Euclid's aim of exposing geometric theorems to a wider audience. According to Byrne himself in the introduction to his work, "I do not introduce colours for the purpose of entertainment, or to amuse by certain combinations of tint and form, but to assist the mind in its researches after truth, to increase the facilities of instruction, and to diffuse permanent knowledge" (1847). In that vein, Byrne also asserted that readers could absorb the content of Elements "in less than one third of the time usually employed" in its retooled form.

Naturally, the world has witnessed quite a bit of innovation since Byrne created his version of Elements in 1847, particularly regarding educational tools. If Byrne had lived today and sought to carry out the same mission, it is likely he would further remediate Elements, as a blog. Indeed, the blog represents the wonderful culmination of the Internet's two foremost uses—information, and communication.

The first precursor to the blog—USENET, a now-obsolete online discussion board—emerged as long ago as 1979 as a platform for distributing information and files (Carvin, 2007). USENET then gave way to numerous similar media, such as the establishment of the email list-serve in 1984, the development of the World Wide Web in 1989, and the publishing of the first website in 1992. In 1994, Justin Hall, a student at Swarthmore, launched what is now acknowledged as the world's first blog, Links.net, presenting the minutiae of his daily life. At the time, Hall referred to Links.net as his "personal homepage." It was not until 1997 that Jorn Barger coined the term "blog," as an abbreviation of "WebLog" (Carvin, 2007).

While the blog was at first slow to take off—in 1999, according to a list compiled by Jesse James Garrett, there were still but a mere 23 blogs online—it soon ballooned in popularity at an astounding rate (Chapman, 2011). In 2005, Garrett Graff became the first blogger to earn White House press credentials, and by 2006, the Internet contained over 50 million blogs! Just a year later, in 2007, the World Wide Web logged over 112 million blogs (Chapman, 2011).

But what exactly is a blog, and what would Byrne's version of Euclid's Elements be like if it were remediated into one? According to an instructive 2006 article in The Economist, "blogging is just another word for having conversations." The article, entitled "It's the links, stupid," posits that blogs surged in popularity due to their ability to engage people and their inner thoughts instantaneously with one another (Economist, 2006). If we adopt the article's definition of blog, a "personal online journal," we must then acknowledge that blogs represent a rather revolutionary shift in the notion of a journal, from a secret catalog of one's thoughts and musings, to a virtual megaphone that sets those thoughts up for public consumption. This shift speaks to the inherent draw of the blog—it connects us to one another, and turns activities that had been solitary exercises into collaborative explorations.

Similarly, converting Byrne's version of Euclid's Elements into a blog would transform the activity of learning geometry and the absorbtion of its proofs and formulae from an individual endeavor into group learning, consonant with broader educational trends. Indeed, one of the most salient features of a blog is that it often contains a comments feature, by which readers can not only engage directly with the author in a near-instantaneous fashion, but also with each other. This allows readers to post questions regarding Euclid's proofs, as well as to suggest answers for one another, a la Quora. In this way, the blog then becomes a virtual classroom. Of course, this shift is not without its potential drawbacks. Classrooms are staffed by teachers who can dispel right from wrong solutions to a problem, and who can help to parse out potentially confusing text. Blogs are open season, wherein readers must use their own judgment when evaluating the accuracy of other comments. Additionally, the student accrues tremendous benefit by struggling through a text and developing his or her own means of understanding it. The student should ideally then confirm this understanding with someone more knowledgeable than he or she, but one should not understate the initial value of this mental exercise. However, the abiity to view a blog with comments that might reveal the inner logic of a proof before a student can independently discern it for him- or herself, has the potential to sap this opportunity.

Perhaps the most prominent difference between Euclid's Elements as a blog as opposed to a colorfully diagrammed codex, though, is the simple fact that a blog is online, rather than a tactile text. While a blog's online preservation through a stable URL circumvents the problem of readers losing access to a text by misplacing a physical copy, or of a text growing so worn-out that it becomes illegible, one cannot annotate a blog or highlight those parts the reader finds most compelling. Moreover, extensive research suggests that we absorb less of what we read through a screen, which could potentially counteract the pedagogical benefit of being able to exchange comments on a blog. However, a great benefit to the fact that blogs are readily accessible online is that they allow for a much greater reach than do the distribution of physical copies. While there is a limit to how many copies of Byrne's version of Euclid's Elements can be printed in a given period of time, there is virtually no limit to how many people could read the blog version of it, and indeed could do so immediately upon the publishing of the blog! This ease of access aligns well with the intentions of both Euclid and Byrne to spread knowledge of geometric principles in the broadest way possible.

Finally, while Byrne's book listed Euclid's theorems in the order in which Euclid presented them, blogs typically present material in reverse chronological order from when it was published. As a result, readers of the blog version of Elements would first view the last set of theorems. While this may not seem significant, we should recall that mathematics is like a ladder, in that to understand it, one must first have ascended through its foundational principles. As a result, if students or readers are exposed to Euclid's final theorems first, they lose out on the exciting process of discovery that comes from building on their knowledge step by step in the order Euclid intended. However, even in a codex form, eager readers may still skip ahead, missing out on this discovery in the same way. Thus, this last point is worth mentioning, but is not necessarily an inherent difference in a blog.

In sum, the blog represents an exciting potential new medium for Euclid's Elements. It may enhance geometric understanding to new heights by creating a virtual classroom, so to speak, or it may stymie learning by precluding self-discovery. Whatever the ultimate result, it is certainly true that the Internet has allowed for countless new educational tools, which have only increased the knowledge base of the world.

Works Cited

Byrne, Oliver. "The first six books of the elements of Euclid, in which coloured diagrams and symbols are used instead of letters for the greater ease of learners." London: Pickering, 1847.

Carvin, Andy. "Timeline: The Life of the Blog." NPR.org. 24 December, 2007. Web.

Chapman, Cameron. "A Brief History of Blogging." Web Designer Depot. 14 March, 2011. Web.

Economist, The. "It's the links, stupid." Economist.org. 20th April, 2006. Web.