The Iliad: A Case Study of Both Successful and Incompatible Media Transfers

When asked to describe The Iliad, the majority of Americans will conjure an image of a book- printed codex, perhaps worn from the generations of high school hands the particular copy may have passed through. Those who remember the text may refer to it as a poem or an epic, recalling the heroic Achilles or the prevailing theme of man’s predetermined fate. However, few recall that the epic did not arise to be read, but rather to be heard; The Iliad is an archetypical work of oral literature.

Though I will argue that the poem has successfully retained its cultural meaning in the transition to a printed medium, I will first consider the tale’s historical origin. A contemporary analysis of The Iliad draws parallels between the poem’s structure and function. Louden underscores the tragedy’s repetitive nature, in which words, lines, and motifs appear habitually. This is crucial to a work of oral tradition, in which adept story-tellers recognize that the audience must be continually reminded of the story’s central themes (Louden 1-8). Additionally, it has been suggested that citizens of a humbler origin, rather than those of a wealthier society, composed the true audience of The Iliad (Dalby 269-279). This claim is accentuated in the text’s inconsistent descriptions of the wealthy, which depict the life of the rich in a manner that would fascinate the lower class, albeit at the expense of exasperating ancient Greek historians (Dalby 279). Finally, the poem is somewhat reminiscent of the Old Testament, consisting of a heroic myth with an air of moral instruction, if one disregards the questionable behaviors of the immortal (Louden 8-9). In summary, The Iliad originally told an oral tale of Greek victory, perhaps with some moral underpinning, to the common people.

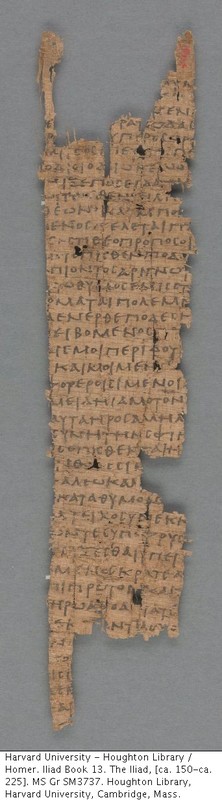

The Houghton Library contains a copy of The Iliad that dates from the second century. The fibers are frayed along the edges of the papyrus manuscript, yet the text itself is straight and perfectly legible. While most readers will read printed, paper translations of the original epic as opposed to papyrus fragments, it is easy to understand the implications of the oral to written media transfer. Perhaps the most significant loss is the lack of community; no longer is one a member of a storyteller’s audience, but rather a sole reader of the text. However, the gain in accessibility nearly compensates, as the epic is now read nearly universally, and it is not difficult to find a fellow scholar to engage in discussion of the work. Moreover, the cultural meaning of the text is still apparent. The reader engages in the events, connects with the characters, and finds lessons in between the lines. As evident by the epic’s continued significance thousands of years after its creation, the Iliad is meaningful and relevant.

Nonetheless, times are changing. The technological revolution has lead some to question whether there will be a technological evolution, with new forms of media replacing the old in a “survival-of-the-fittest”-esque tragedy. While this prediction relies on the use of the slippery slope fallacy, it is not unreasonable to consider the transfer of language and its associated meaning from one medium to another; after all, The Iliad was once simply an oral poem. Thus, I will first consider the media form of an SMS as an entity within itself.

SMS, officially denoted “Short Message Service,” though colloquially referred to as text messages, are an integral form of adolescent information transfer. Most young adults have now grown up alongside this form of media, and its popularity has soared. Josie Bernicot, a French linguist and developmental psychologist, conducted a study on adolescent use of this technology in 2012. Interestingly enough, she found that the average message consisted of 100 of the 160 allowed characters, or roughly 20 words. Roughly an equivalent amount of messages contained relational meaning (i.e., concerning personal relationships) as those that contained informative meaning (i.e., a transactional dialogue). The vast majority (73% of the messages) did not have the “traditional” format of an opening, the message itself, and a closing remark (Bernicot 2012).

Given these statistics about typical SMS usage, it is difficult to imagine the transfer of The Iliad to this media format. There would certainly be a loss of the cultural meaning of the text, as it is impossible to tell the complex tale, consisting of various themes and historical insights, in 160 characters of fewer. Moreover, storytellers of all ages recognize the importance of a clear beginning, middle, and end, and the lack of such an integral format in text messaging would render the story incomplete. Furthermore, there would not be a gain in accessibility even if a poor substitute of the Iliad was rendered via SMS, as we still live in a world in which printed text is more obtainable than an SMS. Therefore, this media transfer is discordant; while one could theoretically attempt to convey The Iliad as an SMS, the product would be too far removed from the original poem to be meaningful.

However, not all is lost. As reasoned by Thorburn and Jenkins, “established and infant systems may co-exist” (2). Just as the printed book will continue to convey the artistic masterpiece that is the Iliad, SMS messages will fulfill functionally relevant niches. Thirty years ago, the thought of a college student writing about The Iliad would be perfectly mundane. However, the thought of one blogging about the incompatibility of the SMS and ancient Greek epics would seem preposterous. Media is certainly changing both the way humans express themselves and the way they view the world. Nevertheless, dialogue itself is constant and timeless; conversation and communication are here to stay.

Works Cited

Bernicot, Josie, et al. "Forms and functions of SMS messages: A study of variations in a corpus written by adolescents." Journal of Pragmatics 44.12 (2012): 1701-1715.

Dalby, Andrew. "The Iliad, the Odyssey and their audiences." The Classical Quarterly (New Series) 45.02 (1995): 269-279.

Louden, Bruce. The Iliad: structure, myth, and meaning. JHU Press, 2006.

Thorburn, David, and Henry Jenkins. "Introduction: towards an aesthetic of transition." Rethinking media change–the aesthetics of transition (2004): 1-16.