Scientific Scrolls: Structural Limitations

Upon hearing the word “astronomy”, most Americans likely envision complex calculations and detailed measurements of stars and planets. In fact, the word does have a very scientific connotation and modern technological innovations give credence to that belief. However, few people can imagine the field of astronomy before such complex tools existed. Astronomicum Caesareum, by Peter Apian, is a prime illustration of the intricate detail and precision required even in the field’s earliest stages. It is not so much a book as it is a scientific guide. Its format as a large book, 18 inches wide and 12 inches in length, is absolutely essential for that purpose.

The book has a very specific goal, and it achieves that goal very effectively. It is an instrument in the form of a book, its pages filled with measurements tools and instructions. Representing contemporary planetary theory, small paper circles called epicycles can be rotated along larger ones called deferents. In fact, Apian had pioneered the use of these movable volvelles. These instruments, or “equatorials” as Apian called them, exist to help calculate the latitude and longitude of the planets at any date and time. The reader, perhaps best referred to as a “user,” can calculate geometric positions and relations using weighted threads extending from the circles. In fact, the book contains instructions for associating calculations with horoscopes to predict auspicious or menacing times to come (Apian, Peter). One particularly remarkable page provides tools for finding the longitude of the planet Mercury. The page has nine printed parts and an intricate infrastructure to allow movement along four discrete axes (Gingerich, Owen).

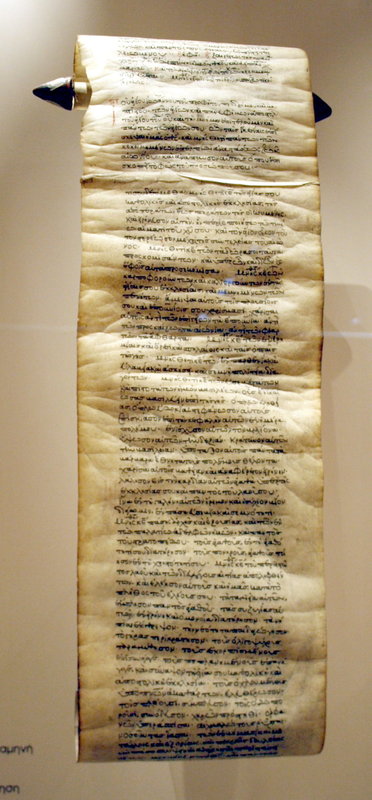

To show how Astronomicum Caesareum and the scroll are vastly different, I will first describe the original purpose of the scroll. Throughout antiquity, the scroll is the standard medium of preserving text. The oldest rolls were made of papyrus, first used about 4000 years B.C. Among the Egyptians, Romans, and Greeks, scrolls were the primary books. Typical uses included edicts, receipts, lists, legal decrees, prayers and poetry (University of Chicago). The standard way of reading the scroll was to unroll it with the right hand, and to hold up the portion that had already been read with the left hand. To give the roll some stiffness, the papyrus was typically wound around a wooden rod with projecting knobs on the end. Usually, the papyrus roll allowed for columns of text each between 25 and 45 lines long, with about half an inch between them (Stilo, Aeilius) The lines were also unmarked, making citation difficult. The scroll was superseded by codex around 400 A.D.

Both the aesthetic and the practical purposes of Astronomicum Caesareum would be lost upon transfer to the scroll format. For a scroll, rolled either vertically or horizontally, it would simply be unfeasible to have pop-out drawings. The delicate, three-dimensional designs present in Astronomicum Caesareum would tear through repeated use, particularly because of the rolling motion inherent in scrolls. In addition, the ease of use that the book format provides would be lost. With the scroll, it would not be easy to flip to a particular page using an index, like a table of contents. A scroll has to be read in a linear fashion, from beginning to end. Ultimately, the scientific material would become less accessible in it’s transfer to a scroll format. The usefulness of Astronomicum Caesareum, unfortunately, would be greatly diminished.

But the formatting differences are overshadowed by the differences between the two media as cultural icons. Astronomicum Caesareum is remarkably representative of its time. All the scientific observations present in it reflect beliefs about the Ptolemaic system, the original theory that the earth, not the sun, is at the center of its universe. In consideration of today’s technological innovations, the book loses it purpose in society because such calculations can be efficiently outsourced to electronic instruments. Complex tools make scientific observations sharper and more automated. On the other hand, the scroll maintains its purpose in society. Describing the losses another poet would face because of his decision not to use a scroll, the 1st century BC philosopher Catallus said, “You shall have no cover dyed with the juice of purple berries – no fit colour is that for mourning; your title shall not be tinged with vermilion nor your paper with cedar oil; and you shall wear no white bosses upon your dark edges. Books of good omen should be decked with such things as these” (Stilo, Aelieus). In other words, the visual qualities of a scroll set it apart. The experience of reading a scroll gives it lasting significance. Web pages are perhaps the modern reincarnation of the scroll, only revealing certain portions of a page in linear fashion.

A scroll is simply not compatible with the original goals of Astronomicum Caesareum. To convert the book into a scroll would be to treat a guide as a story. In the transition itself, the defining qualities of the two media types would be lost entirely.

Works Cited:

Peter Apian, Astronomicum Caesareum (Ingolstadt, 1540) - Museum of the History of Science." Museum of the History of Science. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2016.

Gingerich, Owen. "2." 2. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2016.

University of Chicago. "Coordinating Time." Book Use Book Theory: 1500. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2016.

Houghton Library, Harvard. "A Brief Introduction to Scrolls." Omeka RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2016.

Stilo, Aleius. "Scroll and Codex." Scroll and Codex. N.p., n.d. Web. 07 Feb. 2016.