Transforming the Classics with Modern Media

Transferring media is difficult, particularly from a source that is text-heavy to one that barely displays any words at all. The idea of comparing one of the first bound editions of Homer’s Iliad with twentieth and twenty-first century posters seems almost nonsensical because of their contrasting cultural backgrounds, social contexts, and varying degrees of significance: the Iliad is a symbol of the civilization and culture of Antiquity, while the advertisement for the Woodstock music festival is a significant element of a culture developed centuries after the Iliad’s conception. Somehow, though, differentiating time periods are what make this edition of the Iliad an ideal example of media transformation, in the form of promotional text and image.

This edition of the Iliad functions as a symbol of changing culture. The Western world, after the collapse of the Roman Empire, became a population of illiteracy. Only the very rich and very religious could read, and they read in Latin, sometimes Greek. It took hundreds of years for education to become publicly endorsed by national and local governments, and even then there were restrictions on who could go to school and which languages were considered appropriate for scholars to use. The publication of the Iliad in this time period served as a promotion of the vernacular, English, in place of the Latin and Greek-dominated literature, and ultimately acted as an encouragement of widespread literacy among laypeople.

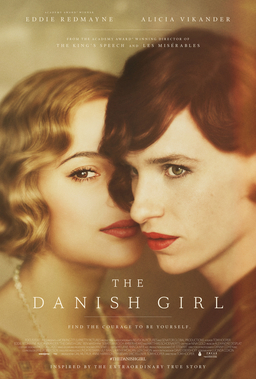

Such ideals are best exemplified through The Danish Girl film poster. In the same way that the Iliad came into print amidst a time of vernacular liberation and literary revolution, the film The Danish Girl was released in accordance with the growing prominence of transgender issues in the United States. The poster’s image, tender and sensual, evokes associations with classical portraiture of the nineteenth century and connects this to a sense of profundity stemming from familiarity with old art and idealized aestheticism. The upper half of the poster’s text, a caption describing the director’s previous works, The King’s Speech and Les Miserables, serves to increase the association, as both films employ related styles of classical era and aestheticism. The lower half, a sort of slogan for the film, “Find The Courage To Be Yourself”, returns to the vein of current events, and conveys a message of modernity and social change despite the years-old setting and style. The Iliad as a poster would convey a similar message of social change, but in terms of literacy and knowledge of classic literature. It would act as an advertisement for the accessibility of formerly bourgeois and scholarly literature, and humbly encourage laypeople to “find the courage to educate [themselves]”. Such a medium would enhance the primary theme of vernacular liberation because the posters would be on public display and therefore, easily available for public viewing. Consequently, although the Iliad is first and foremost a heavily textual product, a film-style poster is as, and if not more, effective than its original medium in getting the point of literary reformation across.

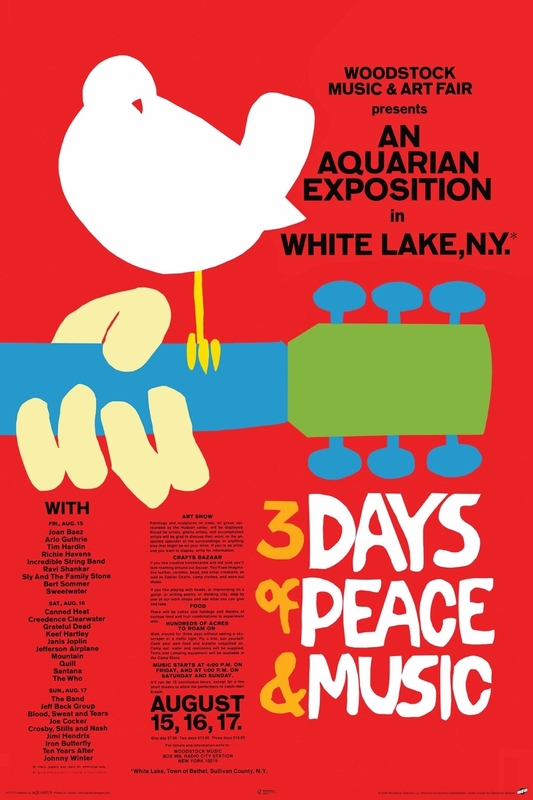

The second poster, an advertisement for the famous music festival Woodstock, also succeeds in imparting ideas of reformation. The festival occurred in 1969, in the midst of much political and social tension in the United States; it was a peaceful, joyous countermovement to all the protests, violence, and foreign conflict. The Woodstock poster jubilantly projects the spirit of the movement through lively colors and designs. More textual than the film poster for The Danish Girl, it describes the occasion, activities and lineups, and even specifies the event by calling it an “Aquarian Exposition”. In this way, the poster imparts a great sense of community. The hippie movement of the sixties, as exemplified through Woodstock, was more than just a political and social reaction. It became a culture and a history of an American people similar to that of an ethnic group or religious sect. The Woodstock poster, as a result, is a historical artifact and a representation of the American hippie-type culture. Likewise, the Iliad is a representation of the history of a civilization little known by the general public at the time of its vernacular reprint. The new edition would have functioned as a way to educate people about Antiquity and perhaps also to build a relationship with current Western culture and the past, in order to elevate or validate beliefs and customs that originated in ancient Greece. Thus, by changing the Iliad into a poster like the one made for the Woodstock music festival, the public would be made aware of ancient Greek culture—along with its history, mythology, and values—in a language the public understood. The problem with this, though, is that certain images and terminology would not be familiar to laypeople who had never heard of the Iliad or ancient Greek civilization, whereas during the sixties, because of advances in technology that facilitated communication and the spread of news, the average person would have understood the context of Woodstock and its advertisements. Such a poster would only succeed in projecting culture and beliefs if the audience were somewhat familiar with the classics, but without an awareness, the message is lost, and the novel is made even more inaccessible.

The third type of poster is essentially a combination of the two previous ones, imposing upon its audience both cultural and sociopolitical perspective. The only difference between it and the others is that its significance changed over time. Consisting only of the phrase, “Keep Calm and Carry On”, the poster was commissioned in 1939 by the government of the United Kingdom in response to national panic over the impending war. The government did not typically display this poster in public spaces, and soon it was abandoned and later forgotten until 2000, when British shop owners discovered an original version of the “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster. What started out as an effort to boost public morale in a time of war became a collection of imitations modified to fit circumstances shaped by popular culture. The context of the poster was inherently transformed, and today its original meaning is hardly known by the average person. The simplicity of the poster makes it malleable—its slogan is so short and ambiguous that it could be applicable to almost any situation. If the Iliad were to be fashioned into a similar poster, its significance would also be lost; the novel requires too much context to reduce itself to such an unspecific phrase, and if recreated as “Keep Calm and Read the Iliad”, there would be nothing revolutionary to advertise.

Despite this, evolution, specifically of culture and context, is an important part of transferring media. The Iliad’s English edition symbolized the evolution of language, and the evolution of nationalism in the form of language. It also signified a transforming culture, one that would go on to develop a written standardization of colloquial speech and a greater awareness of its own classical origins. The posters for the film The Danish Girl, Woodstock, and “Keep Calm and Carry On” all evolve meaning through the content they attempt to publicize and the public’s initial awareness. The Iliad is different because it can attempt to publicize itself with familiar formats, both textually and aesthetically, but it cannot feed off of its audience’s assumed knowledge because it is meant to provide or enhance that knowledge. Thus, in the process of transferring media, the purpose of advertising a literary reformation is lost through evolution, but retained by sociopolitical, cultural, or historical significance.