An Experience Reimagined

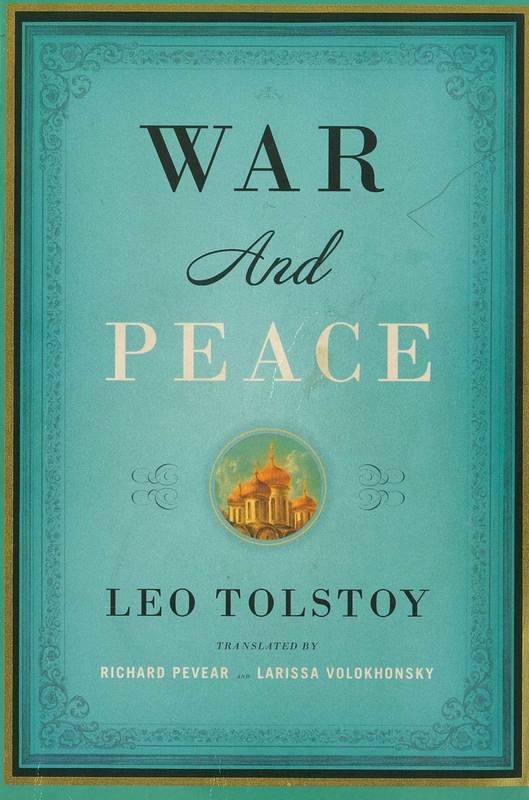

“Historical facts, as we saw, presuppose some measure of interpretation” states E.H. Carr in What is History?. He seems to suggest that, over time, the analysis of concrete events is actually the result of the fluidity inherent in value judgments. This subjective judgment is exactly the type of analysis that Tolstoy points out and guards against in his novel War and Peace. The two novels have very similar messages. Not only does Tolstoy’s work implement Carr’s principles nearly perfectly, but Tolstoy’s work also describes the typical perspective of the historical novel on the Battle of Borodino, thereby illustrating the differences between the typical and ideal historical novel.

Carr argues in What is History? that historical facts are intrinsically dependent on interpretation, and that interpretation itself is based on moral judgments. He also claims that when people who have been affected by an individual are still alive, it is difficult for one to judge that individual as a historian would judge that individual. The people around you have opinions on that particular individual, so your opinions are affected by those peoples’ opinions. Following this logic, first-hand accounts written by people who were actually present at an event are biased. Carr argues that historians should judge events and institutions, not individuals. He claims that blaming individuals provides alibis for entire societies. He also describes history as “a process of struggle” where change always benefits some groups of people at the expense of other groups of people. This is often described as the “price of revolution.”

Tolstoy’s novel implements Carr’s principals very well. He illustrates Carr’s point that interpretation leads to fact. In Subchapter XXVII, Tolstoy describes Napoleon’s precise instructions to the French army prior to the battle. Tolstoy writes, “This disposition, which French historians speak of with rapture and other historians with deep respect, was the following” (781). Subsequently, he explains how historians typically portray Napoleon’s instructions given to the men before the Battle of Borodino as being the work of pure genius and as the primary reason behind the victory. Tolstoy then goes on to show that “None of the instructions of the disposition were or could be carried out” (783). This illustrates Carr’s point that interpretation leads to fact. The interpretation of Napoleon’s instructions as being the sole reason behind victory has lead to the perceived fact that Napoleon was the master general. Thus, Tolstoy has illustrated the difference between the interpretation of historians at the time and his own more recent interpretation.

Tolstoy illustrates Carr’s point that historians should judge whole societies, not just individuals. Tolstoy shows that Napoleon is not actually responsible for the perceived victory of the French army. Residing over a mile away from the actual battle, Napoleon receives incomplete information and “On the weight of such unavoidably false reports, Napoleon gave his instructions, which either had been carried out before he even gave them or were not and could not be carried out” (800). This is a very surprising portrayal of the generals, a stark contrast to the traditional portrayal of generals as masters of their armies. This is the logical complement to Carr’s argument. Carr would argue that Napoleon cannot be blamed for the atrocities since he is a single individual. Tolstoy’s argument completes the circle. If Napoleon cannot receive the blame, then he cannot cannot receive the credit either. Together, the arguments of the two authors suggest that history books that identify Napoleon as the prime cause of either the success or failure of the French army are inaccurate.

Tolstoy illustrates Carr’s point that the judgment of people alive during an historical event is different from the judgment of people today. From the present perspective, it seems that Napoleon should have pursued the French army and defeated the few soldiers that were left. However, from the perspective of him and his generals at the time, the spirit of the French soldiers was broken. Tolstoy writes, “Some historians say that Napoleon needed only to send in his intact old guard for the battle to be won. It is not that Napoleon did not send in his guard because he did not want to, but that it could not be done. All the generals, officers, and soldiers of the French army knew that it could not be done, because the army’s fallen spirits did not allow it” (819). This “spirit” of the troops can only be discerned by someone actually present at the time. Only someone present in that moment could discern that the moral resolve of the army was depleted. Someone alive at the time would arrive at a different conclusion than the typical historian writing years later would reach. This difference fits Carr’s argument that present judgment is different from past judgment.

Carr sets expectations for the historical novel that Tolstoy meets. Tolstoy illustrates that interpretation leads to fact, that societies rather than individuals should be judged and that present judgment differs from past judgment. The two texts complement one another very well. Tolstoy’s novel reveals how the principles outlined in Carr’s work are implemented in practice.

Works Cited:

Carr, E.H. What is History? Cambridge University Press, 1961. Print.

Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace. N.p., n.d., 1869. Print.