The Perception of Realism

“History… is information about human social organization” (1) claims Ibn Khaldun in the Muqaddimah. While Khaldun argues that historical information is primarily rooted in factual occurrences, he suggests that untruth tarnishes the majority of transmitted accounts. Only via “critical investigation” (3) may one untangle reality from the falsehoods. However, it is impossible to define a state of reality, as reality is ingrained in individual perceptions of the way in which the world works. Thus, as argued by Hayden White in Metahistory, reality is fluid across both space and time. Therefore, there is no such thing as a “realist” or “objective” historical account, as realism is itself subjective. Nonetheless, this does not imply that history is a fiction; rather, it is a chronicle recorded via a perceptual lens that must be considered when interpreting a source.

Khaldun works under the premise that historical inaccuracies arise from two major wrongdoings: partisanship and the misunderstanding of the way in which human civilization functions. Of the two, partisanship is perhaps the more easily identifiable because it “obscure[s] the critical faculty and preclude[s] critical investigation” (1). Ultimately, recognizing implicit biases in a historical source is not an unmanageable task. Moreover, it is universally accepted that prejudiced historical accounts are flawed in their stretched versions of the truth.

On the other hand, the characterization of ignorance of reality is far subtler, rendering Khaldun’s judgment of others’ scholarly accounts inconsistent. He provides multiple components of this historical offense; some, such as to “embellish conditions and spread the fame (of great men)” (2) are more credibly flawed. Other definitions that Khaldun provides are questionable. When he considers “ignorance of how conditions conform with reality” (1) and “ignorance of the nature of the various conditions arising in civilization” (2) to be shortcomings among the majority of historians, the critical reader must question Khaldun’s own perception of reality.

Relatedly, White suggests that “convictions of [one’s] own capacities to know ‘reality’” (46) underscore the majority of significant philosophical disputes. While an understanding of reality is unanimously desirable, and, in fact, essential to maintain credibility, reality is relative. Therefore, Khaldun’s critique of historians’ misconstructions is archetypical of the arguments regarding “which group might claim the right to determine of what a ‘realistic’ representation of social reality” (46) is. White’s metahistorical analysis reveals a logical fallacy in Khaldun’s reasoning; he fails to recognize that, objectively, there is no justification as to why his own understanding of the way in which the world works is better that that of his contemporaries.

Nevertheless, Khaldun’s emphasis on a grasp of reality is not unfounded, as he points to multiple examples in which historical accounts are scientifically or physically impossible. For instance, he uses AlMas’udi’s description of Alexander’s conquest of sea monsters to illustrate a tale “made up of nonsensical elements which are absurd” (2). Specifically, Khaldun emphasizes the inability for a human being to remain underwater for such a long duration, and thus convincingly debunk this account (2). Accordingly, Khaldun’s emphasis on realism is justified when considering the most extreme and improbable (if not impossible) historical narratives, which lack authenticity.

Within the shades of grey, intermediate between the boundaries of possibility and impossibility, Khaldun’s reasoning cannot be upheld. While it is feasible to disprove that an outlandish event occurred, one cannot discount a particular interpretation about the “purpose of a [historical] event” (1). A multitude of plausible realities exist via the unique perceptions each scholar brings to the study of the past, and their validities cannot truly be compared. White describes this historical discourse when stating that there are “many different conceptions of ‘historical realism’…contending for hegemony” (47). Consequently, the belief in the objective historical account truly suggests a misunderstanding of reality, as both reality and history are subject to the lens of one’s conceptualization of the world.

While this interpretation of historiography may appear superficially dismal, it merely points to the fact that one’s critical analysis of historical sources is paramount. Perhaps the most meaningful trait in a historical scholar is the ability to understand the context surrounding not simply the historical event of study, but also the mindset of the source’s author during the creation of the source. Via this cyclical manner, history is revised and scholarly discourse continues. Consequently, history is not a fiction, but rather a conversation as to how and why the truth played out in the past.

Works Cited

Khaldūn, Ibn. The Muqaddimah; an Introduction to History. Trans. Franz Rosenthal. New York: Pantheon, 1958. Print.

Liew, Han Hsien. Hayden White. Digital image. Academic Writing as Storytelling. The Wesleyan Writing Blog, 28 Apr. 2011. Web. 1 Apr. 2016.

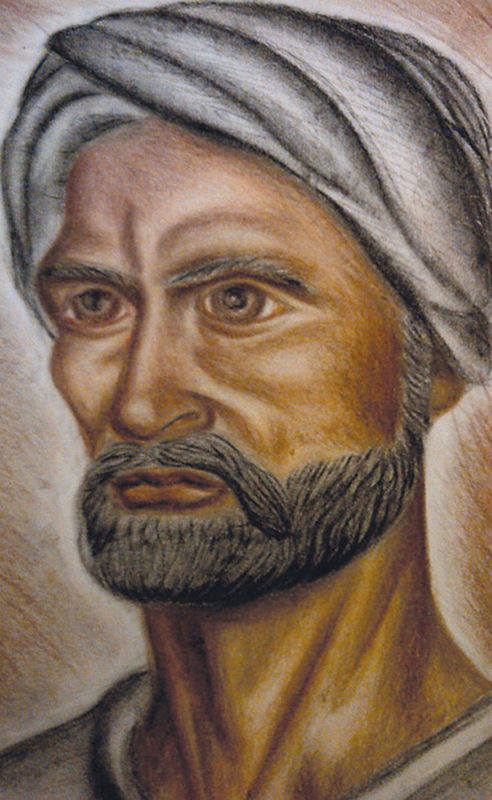

A portrait of Ibn Khaldun. Digital image. Wikimedia Commons. MediaWiki, 2 Aug. 2013. Web. 1 Apr. 2016.

White, Hayden V. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-century Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1973. Print.