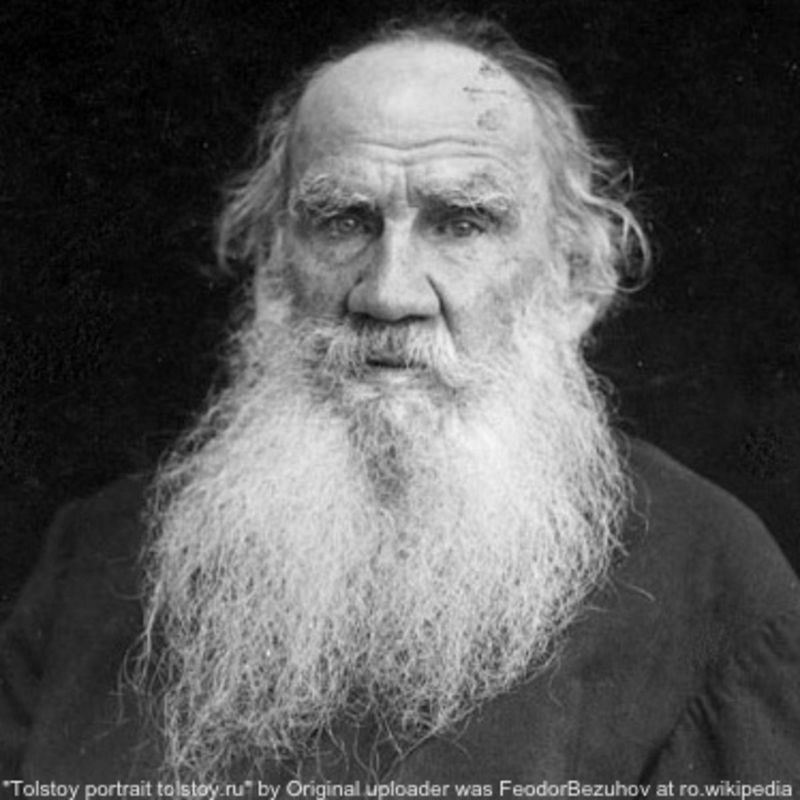

Tolstoy's seemingly Contradictory Treatment of History

Chapter 26 of War and Peace deals with the eve of the Battle of Borodino. Tolstoy, a Russian writer, has connections with the Russian side of the conflict, so we would expect him to have a bias towards Russian forces in this historical retelling. As it is impossible to recount every single detail of every single moment in history, all history is not completely true. If we define history as a written or otherwise communicated account of the past, then there is already a degree of separation between an event which happened in the past and how someone studying history will experience it. The scholar perusing through historical texts must understand the past event through the lens of a historian, who has made many choices about what details from an event are important enough or relevant enough to include in a history. So a perfectly “objective” or “realist” historical account cannot exist. Imagine trying to give a historical account of reading this paper. It would be nearly impossible to describe all of the sensory phenomena associated with even simple tasks. Basically, when we study events in the past, we are seeing them through a filter established by whoever compiled the history.

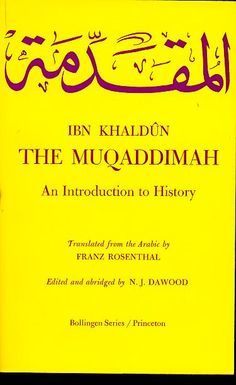

Ibn Khaldun calls this particular intrinsic flaw of history “reliance upon transmitters” which “makes untruth unavoidable”. However, this does not mean that history is not worth studying. This characteristic of history actually allows us to learn something which we would not be able to learn if history was a perfectly unbiased retelling of the past. Thanks to history’s reliance upon transmitters, we can learn about the priorities of authors of a history by studying what they include in a retelling! Michel de Certeau discusses the notion of history being dependent on language in The Writing of History. Events in the past occur independently of language, but history cannot be recorded without language. This disparity contributes to the intrinsic unreliability of history. Tolstoy realizes that a completely true perspective on history is impossible, so he decides to not try to give a macro-level retelling of history, but rather to detail Napoleon’s experiences on the eve of the Battle of Borodino in order to concede that his retelling is missing components. Tolstoy instead uses a historical retelling to convince us of his own theories.

Tolstoy’s retelling of the eve of the Battle of Borodino in Chapter 26 of War and Peace is from the perspective of the French army. It is curious how he focuses this part of his narrative on Napoleon’s activities before the battle, while in Chapter 28, he discusses how history is not determined by the will of certain “great” people like Napoleon or Peter I, but by the collective will of individuals. Tolstoy argues that it is ridiculous to think that the Battle of Borodino could have been decided by Napoleon having a cold. He proposes that even if Napoleon had given the order to not fight the Battle of Borodino, his army would have disobeyed his orders and fought it anyways. How can we resolve this contradiction between Tolstoy giving us a narrative focused on Napoleon and his diminishment of the influence of a single person in the course of history? Perhaps Tolstoy chose to tell the history of the Battle of Borodino’s prelude through a Napoleonic narrative, because that is the most succinct way to give a narrative. It would be much more complicated to create and arguably less interesting to read a history which focused on the lives of individuals in the French army. Tolstoy could have written a general narrative for a “common” soldier in the army, but there is probably much less documentation for any individual when compared to the amount of historical content focused on Napoleon. Also, any history of a typical soldier in the army would no doubt also include references to Napoleon. So by focusing on Napoleon, Tolstoy is recognizing the large amount of influence that Napoleon had over individuals in his army. Thus, to some extent, a telling of the story of Napoleon might be an effective way to convey the experiences of individuals in his army. In Chapter 26, Tolstoy portrays Napoleon as a human with relatable concerns, not like a god-figure. Napoleon is described as “Snorting and grunting” with a “fat back” with a “fat, hairy chest”. Tolstoy could have had multiple motivations for including these details. On one hand, we might interpret that he has a bias against Napoleon and the French since he is Russian. A more cohesive explanation is that Tolstoy is humanizing Napoleon. It is easier to be convinced of Tolstoy’s theory in Chapter 28 if we understand Napoleon as a person with emotions rather than an un-relatable supreme leader. Tolstoy shows that Napoleon had concerns about his actions, like any of us would in the scene about the painting of his son in which “[Napoleon] felt that what he said and did now – was history.” Tolstoy’s narrative about Napoleon both gives a distant idea of soldiers’ experiences while also contributing to his later argument about influential people not deterministically dictating history.