The Scientific Analysis of History: Revealing What Is Real and True

Learning and understanding history has driven the development of modern cultures, societies, and civilizations. Yet as history is often told as stories, with varied perspectives and accounts of past events, the path to finding the truth has not been a clear one. How can it be determined whether one version of history is more accurate than another? In their pursuit of the truth, historians have adopted their own preferred methods for finding answers to such questions. From the 12th to the 20th century, historians have offered disparate solutions for understanding the past.

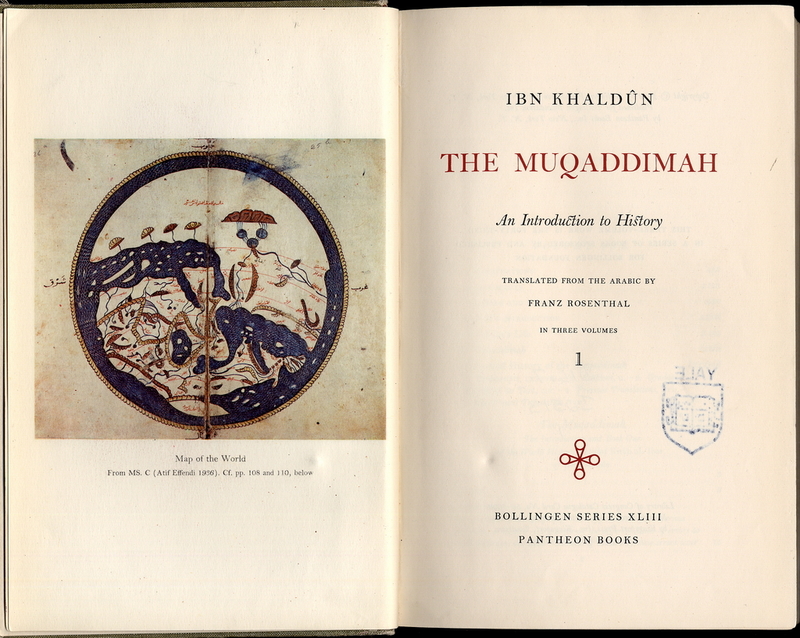

In the study of history, much of the uncertainty and variability in recorded events stems from elements of language, including diction, syntax, and perspective. To overcome these difficulties, Ibn Khaldun proposed one of the earliest methods of analysis in 1377 with his work The Muqadimmah. In the preliminary remarks of his book, Khaldun recommended an “independent” and “entirely original science” for understanding past civilizations. He put forth the idea that history, “as it is with any other science, whether it be a conventional or an intellectual one,” (Khaldun) required a methodological manner of study in order to gain an objective knowledge of the past. Such studies had been limited, he suggested, because scholars did not appreciate the inherent difficulties of finding simple, objective truth in historical accounts (Khaldun). Rather than taking such accounts as fact, Khaldun acknowledged the importance and necessity of utilizing a scientific method to analyze the information.

Almost seven centuries later, historian Hayden White published his book Metahistory, in which he argued that the study of the past could not be conducted with scientific methods of analysis. In stark contrast with Khaldun, White opposed scientific methods for much of the same reasons that Khaldun supported such methods. White believed that the inherent literariness of history required a different set of methods, skills, and tools (White). In White’s words, the challenges of understanding history were “not presented in the human effort to comprehend the world of merely physical process.” (White, 45) While physical, scientific processes might be easily replicated to gain a better understanding of the facts, historians relied on personal, often biased, interpretations of events from which facts could be difficult to extract. Thus, White argued that a scientific method of observation and analysis would not be applicable.

Taking these two historians’ texts in conversation, Khaldun may have responded that the problems and difficulties in studying history should not preclude it from scientific analysis. A scientific method could provide a more standardized practice for understanding history and allow for objectivity in an otherwise subjective field. In contrast, White argued that the subjectivity of history was precisely the reason why it required its own method of analysis. Analysis of the “data of history, society, and human nature” (White, 45) would require different interpretations of language and morality compared to that of science. Yet the method Khaldun proposed did not ignore this either, as he encouraged scholars to distinguish “possibility” from “absurdity” with “personality criticism” (Khaldun). He realized that historical accounts could be influenced by personal biases, which should lead to questioning during analyses. The difficulties that White identified in the study of history were very similar to those identified by Khaldun, and both historians maintained a similar goal, in the search of what was “real” and true in a historical account.

Although White and Khaldun did not agree on their methods, they did share the belief that the study of the past was a search for historical truth and reality. Both historians saw the need to find legitimacy in historical accounts by considering whether or not the accounts represented plausible events. According to White, this required a comparison to “unrealism or utopianism,” (47) and Khaldun similarly suggested scholars to consider the “conformity of the reported information with general conditions [of society].” (Khaldun) The historians believed that the true facts of an event could be revealed when considered in the context of the society and civilization in which it occurred. In addition to making comparisons with realistic experiences, this would reveal the accuracy of a historical account. Although the historians may have disagreed on the exact methods of pursuing truth, the forms of analysis they supported were actually quite similar. Across the time span of seven hundred years, these historians' commitment to searching for true facts of the past has persisted.

References

Khaldūn, Ibn. The Muqaddimah: an introduction to history; in three volumes. 1. Eds. Franz Rosenthal, and Nessim Joseph Dawood. No. 43. Princeton University Press, 1969.

White, Hayden. Metahistory: the historical imagination in nineteenth-century Europe. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University, 1973, p 45-47.