Metamorphosis: Monster in the Mirror

Jonathan Culler states, “The fictionality of literature separates language from other contexts in which it might be used and leaves the work’s relation to the world open to interpretation,” (33) in Literary Theory: A Short Introduction. While modern interpretations of Kafka’s Metamorphosis range from statements about the working world to Halloween horror stories, the book was actually a mirror of the ethno-political conflicts and feelings of alienation experienced by Kafka and other Jewish people in Prague during the early 20th century.

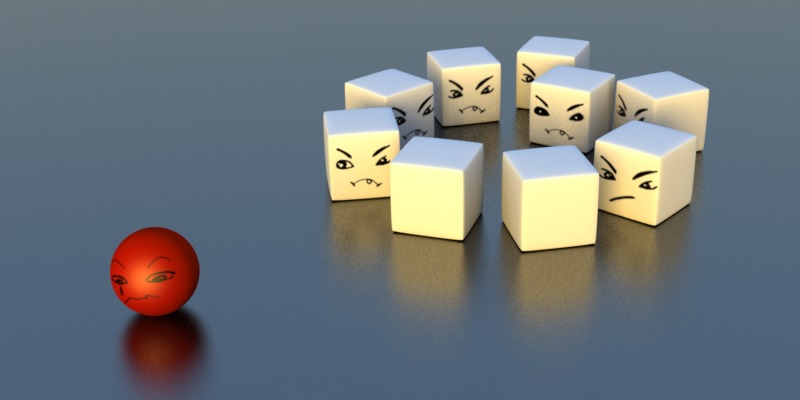

Franz Kafka was born in 1883 in Prague, Bohemia. His family was Jewish but they rarely attended synagogue. Prague’s Jews, including Kafka, conducted business in German, spoke German, read German literature and attended German plays. The Czech working class majority viewed Jews as outsiders because they were “German” and and because they were Jews (UPenn).

Since the 16th century the Czechs, including Jewish people like Kafka’s family, had struggled for ethnic identity and self-determination, forced to live in Bohemia. The Habsburg monarchy controlled the Austro-Hungarian empire, which included the Czechs in Bohemia and the neighboring Slovaks in Hungary. Both the Czechs and the Slovaks suffered from extremely repressive ethnic and religious policies and the region had a long history of political strife (Boeckh).

In Bohemia, an industrial revolution had created a society for the Czechs that included intellectuals, a middle class and industrial workers. The Czech national revival was influenced by the Enlightenment and romanticism and led to a National Museum and a National Theatre. By the early 20th Century, Czechs were making political demands, including the recreation of an independent Bohemian kingdom. Bohemian Germans strongly opposed the Czech cultural achievements, fearing the loss of their privileged position (Boeckh).

The Slovaks were far less culturally sophisticated and economically integrated than the Czechs. The Slovaks did not have any platform for political expression, and they did not receive a national revival nearly as prominent as the Czechs’. They were less industrialized, led only by a small group of intellectuals (Jelen). Tensions throughout the empire reached a peak on the eve of World War I, when Kafka’s Metamorphosis was published.

Mirroring these conflicts, Greg represents the Slovaks and his family represents the Czechs. Together, they fight poverty, or the Austro-Hungarian empire, but there are still differences between Greg and his mother, father and sister. Representing the contemporary Slovakian citizen, Greg is highly repressed by the long hours and demands of his insurance job, unable to pursue personal hobbies. His family is the Czech Republic, initially insulated from the full effects of poverty because of Greg’s efforts and thus able to live a comfortable existence in a spacious apartment. His sister even pursues the cultural endeavor of learning the violin, a potential student at the Conservatory. Gregor’s unexpected plight throws them into a difficult fight against poverty, just as the Czechs and Slovaks would be forced to fight in World War I through no fault of their own. The father must return to work and Gregor’s sister must care for him, and the family is forced to sell many of their possessions. They grow to resent Gregor and view him as the source of their troubles, foregoing any gratitude for the financial support he had offered them earlier. The family, and the Czechs and the Slovaks, are united only temporarily in their fight against poverty and in the war, respectively.

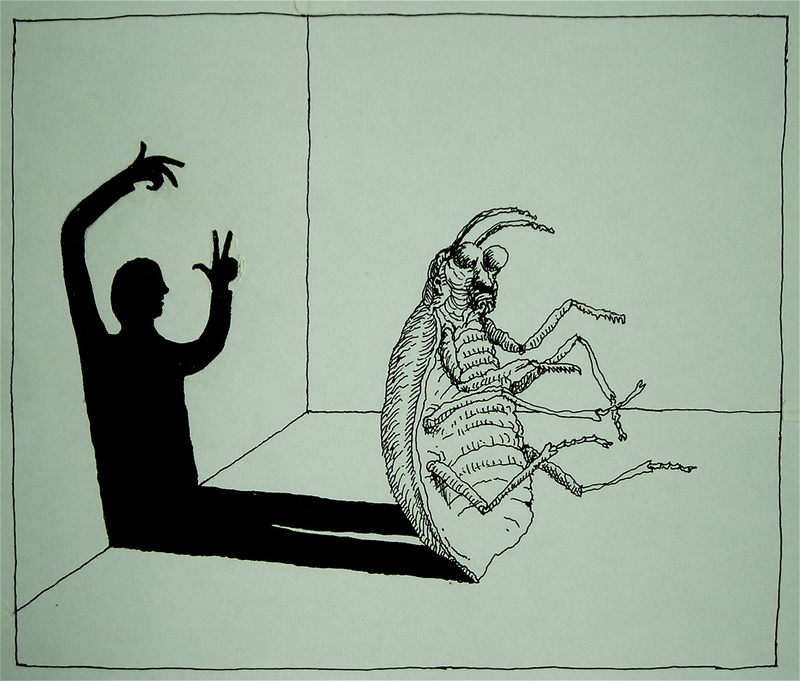

A Jewish writer in Prague, Kafka had experienced firsthand clashes between Czech, German and Slovakian languages (UPenn). The loss of language, experienced by Gregor, represented the loss of what makes us human. When Gregor speaks he only frightens his family members. He longs to tell his sister, for example, of his plans to send her to the Conservatory but is tortured by his inability to communicate with his family. He can only hope, for example, that his sister recognizes his food preferences and he has to cover a painting with his body to prevent his mother from taking it from his room. He is isolated, physically and in thought, because of forces beyond his control.

After the dust has settled and World War I ended, the independent state of Czechoslovakia was formed. The political maneuvering of the Czech National Council leader Masayrk has convinced the Allies to grant the Czechs this wish (Gawdiak). The Slovaks, without an independent state, are sent there, although cultural differences persist for many years afterwards. Likewise, Gregor’s struggle paves the way for his sister’s independence. In caring for Gregor, she has assumed adult-like responsibilities, and by the end of the novel she has blossomed into a beautiful young girl, experiencing a transformation opposite that of Gregor. The fall of the Slovaks is the rise of the Czechs.

From the physical world around him to his revolutionary world at the time, Kafka uses Gregor to communicate his hopeless existence and isolation felt by him and so many other Jews in Czechoslovakia in the early 20th century. The novel ends on a hopeful, yet sardonic, note. Gregor's sister has transformed too, just as the Czechoslovakians gained dominance as an independent state in the end. Thus, Kafka’s Metamorphosis indicates that a blight for one group can be a windfall for another one in a world that cannot be fully controlled.

Works Cited:

Boeckh, Katrin. "Crumbling of Empires and Emerging States: Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia as (Multi)national Countries." New Articles RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Gawdiak, Ihor. "Czech Republic - World War I." Czech Republic - World War I. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Herold, Axel. Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Deutschen'. Munich: Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag. 1993. p. 1486. ISBN 3423325119.

Jelen, Natalia. "20th Century." 20th Century. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

Nervi, Mauro. "Kafka's Life (1883-1924)." The Kafka Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.

UPenn. "Penn Reading Project." Penn Reading Project. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Feb. 2016.