The Turn of the Screw: A Statement on Narrative Authority in Victorian Society

In The Turn of the Screw by Henry James, the characters withhold much of their interior lives from both one another and from the reader. This helps to create a parable replete with suspense, a quality of many well-crafted stories. While James’ novella skillfully embodies the important virtues of a well-received story—reflected in the first line of the narrative, “The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless” (James 22)—he demonstrates a uniquely deliberate control over what he has written, a conspicuous ownership over the characters he created and the stories they tell. The prologue that he includes sets up the core of the novella as a tale being told orally. It is therefore unclear from the start who the narrator of the story is: it could be the governess narrating, the orator relating the story to a group of frightened friends, or perhaps even James himself acting as the puppeteer of the characters that he created. As the 19th century was a time in which folklores and fairytales were popular, and science was supplanting religion as an accurate source of information about the past and natural phenomena, James’s novella challenges readers to question the role of storytelling in the Victorian era. Specifically, he prompts readers to question the concept of narrative authority: who has the power to tell a veracious account, replete both shocking facts and stories left unexplained.

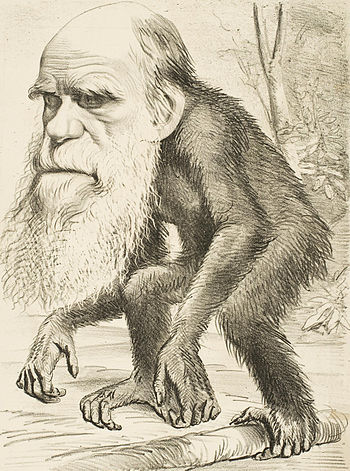

With the advent of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, which trumped “the traditionally religious story” of the Bible, the British population of the late 19th century undoubtedly struggled to identify who indeed has the authority to dictate a story and claim it as fact; perhaps James’s novel contemplates this confounding of narrative authority by failing to provide a distinct narrator to the story he tells. He sets up The Turn of the Screw as story read out loud, much like the fairytales and folktales of the Victorian era. Moreover, its structure—a story in a story—makes it more difficult for readers to trace the tale’s sources of unreliability and inaccuracy. The governess suggests that she misconstrued events upon writing down her story; for instance, upon relating information regarding her ghost sightings to Mrs. Grose, she says that she “could give no intelligible account” (James 55) of her surreal encounters, as they contrast so starkly with the mundane experiences of the other characters—and the reader. It is also possible that upon telling the tale to his audience, Douglas adds his own inflections, emotions and biases to the narrative, influencing the final product. When he introduces his story, he states, “If the child gives the effect of another turn of the screw, what do you say to two children” (James 23), as though he has the power to effortlessly alter a story—tacking on a second child—in order to achieve a dramatic and convincing effect. This structure, conducive to a lack of a reliable, lucid narrator figure, allows the reader to contemplate who has the control over the stories that society chooses to believe, and even suggests that no single figure with such authority can exist.

It is interesting that while James constructs a particularly thrilling novella, he deliberately sets premises for captivating stories, yet refrains from relating them. This aspect of The Turn of the Screw further confounds who indeed is telling the story, as characters deliberately withhold critical information from one another. James insinuates a sensational backstory accompanying the deaths of Miss Jessel and Peter Quint, but creates characters that stubbornly refuse to share this story. Moreover, he crafted the novella so that readers do not know why Miles was expelled from school, or why he dies at the end of the story. By placing the blame of these gaps in the story upon the characters—Miles is reticent regarding his misconduct, and the governess stops writing her story at an especially pivotal moment—he extricates himself from the faults in the story he himself is telling. James, known through his writing to be a realist, thus makes a statement regarding the frustrations among people of the late 19th century toward the contradicting narratives that science and religion presented; both realms of understanding the world are replete with gaps in knowledge, as phenomena exist that neither can explain.

However, the reader has insight that the characters within the novella do not, an awareness that it is James himself who has deliberately omitted closure that is typical of a satisfying story. The reader thus reflects on how James may be intentionally flaunting—or even mocking—story telling conventions. As Jonathan Culler writes, a text could be interpreted either as the author had intended, or independently of the author’s ideas. Perhaps by setting up a story in which both the narrator and events are ambiguous, James prods readers to question the act of storytelling itself; the opposing facets of interpretation that his story presents mirrors the responsibility of his 19th century audience to compromise between the opposing narratives of science and religion, and personally determine the most truthful account—a form closure to human society’s story.

Work Cited

Chaves, Oscar M. “The Darwinian Revolution.” REVISTA CHILENA DE HISTORIA NATURAL

83 (2010): 237-241. Hollis. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

Elshakry, Marwa. “Global Darwin: eastern Enchantment.” Nature 461.7268 (2009): 1200-1.

Hollis. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.

Harris, Jason Marc. Folklore and the Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction.

Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2008. Google book search. Web. 21 Feb. 2016.

“Henry James, the Realist: An Appreciation.” The Methodist Review (1885-1931) May 1918,

34.3: 410. Proquest. Web. 23 Feb. 2016.

Ryba, Thomas. “COMPARATIVE RELIGION, TAXONOMIES AND 19TH CENTURY

PHILOSOPHIES OF SCIENCE: CHANTEPIE DE LA SAUSSAYE AND TIELE.” Brill Online Books and Journals 48.3 (2001): 309-338. Hollis. Web. 22 Feb. 2016.